The Anxious Generation Part One: How social media apps rewire the teenage mind

For years I have believed social media is about the worst thing to happen to teenagers since the Children’s Crusade of 1212. But it is worse than I thought.

Jonathan Haidt’s new book The Anxious Generation makes a strong case that social media and online activity is fundamentally changing the brains of both boys and girls.

I will write to you three times this week on this topic, and eventually I will come to what can be done about it in addition to our phone ban and information sessions at school – because there are plenty of opportunities in our corner of the world to protect our children from the worst of it. But let’s have a look at why Haidt calls it a ‘rewiring of the mind’.

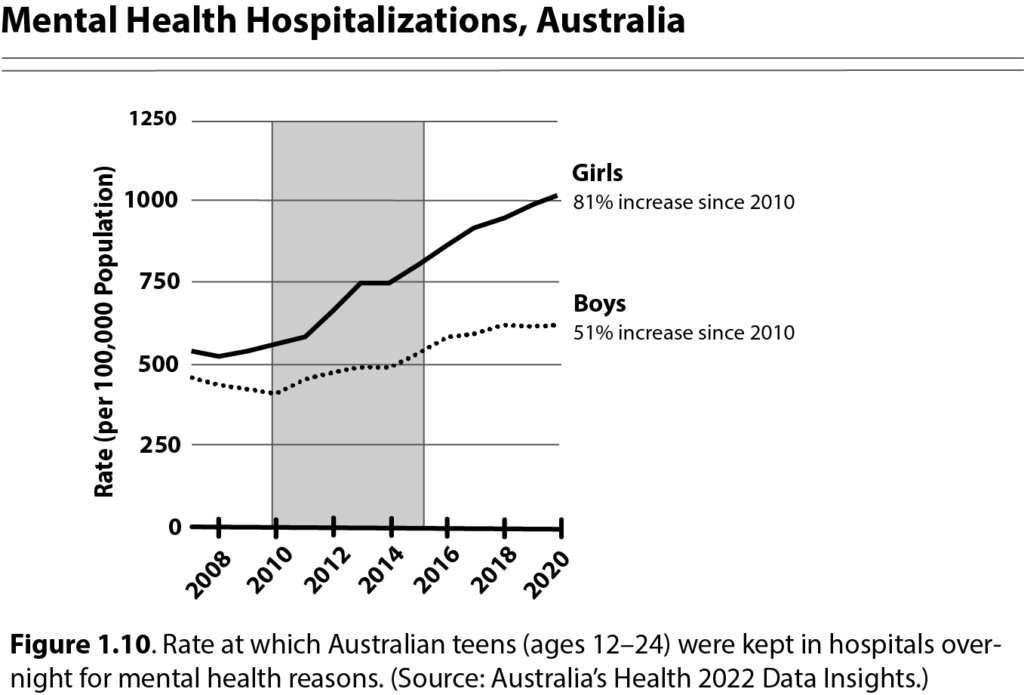

The data is unambiguous: more young people in this generation are becoming more anxious, depressed and lonely than their parents and grandparents. The graph below shows mental health hospitalisations from 2010 to 2020 in Australia before Covid. It is one of dozens of similar graphs in Haidt’s book that establish this rise in anxiety across the Anglosphere. With data this clear we should look for a cause, or a range of causes, so we can help.

Haidt says 9/11 or terrorism or climate change fears have not caused this rise. Those dangers were around 15 years ago – and some were even worse then. The increase in anxiety starts to really increase in the early 2010s. This is when the first iPhones came out. It is also when Instagram – a social media platform that couldn’t (originally) be used on a computer – was launched.

This is where our Year 8 critical thinking students would hopefully call out ‘Post Hoc Ergo Proctor Hoc’ – just because one thing happened after another, it doesn’t mean the first caused the second. We have to look for causation not just correlation. Haidt pointed this out back in 2017. But he says that now, in 2024, there is enough evidence to show that social media and overuse of phones is causing the problem of anxiety … because it is ‘rewiring’ the teenage brain. Indeed, he calls it the ‘Great Rewiring’ of 2012-2017.

Young people for many years have had two innate brain wirings that help them learn about their surroundings and culture – conformist bias and prestige bias. They look at what everyone else is doing in their community (conformist). And they assess what seems to result in the best social and societal status (prestige).

Social media hijacks both. Many kids now want to conform to what they see online as much as – or more – than in their own neighbourhoods, and that means the images, attitudes and views that flood their consciousness as they doom scroll for hours. It used to take several weeks for someone to take stock of their new surroundings. With social media, it takes three seconds for each post. As Haidt says, social media platforms are ‘the most efficient conformity engines ever invented’.

Prestige bias then prompts young people to want to compete with the completely unrealistic standards they see. They see images and stories of more beautiful (touched up) people – even the more popular group in their school – having ‘better’, more popular lives. Even if they consciously know not everyone is spending their lives sipping pina coladas on the beach, the subconscious can still chip away at their confidence.

And there’s no let up. Personalised algorithms mean influencers follow them as they go home, as they sit alone in their house, as they go to bed at the end of night. There is no leaving the bullies at school. Once, people usually (but not always) got prestige from being good, or even excellent, at something. But influencers get prestige from hundreds of thousands of vapid clicks.

The brain’s wiring can be flicked to a positive ‘discover’ mode, which makes a person curious, full of learning and brave about their surroundings, or into ‘defend’ mode, which makes them fear harm, stay ‘safe’ and keep out of the way. Social media keeps many people in defend mode: they don’t explore the world for themselves, they feel marginalised and they hide behind a screen even in social situations. This is even more rewiring that causes anxiety and depression.

Then there is the addictive potential of social media. Once we’re in, we want more and more. The ‘swipe’ motion delivers an endless little hit of dopamine. It gets harder and harder to take mobiles out of our hands.

I have even found this as a man in his mid-50s. Earlier this year I literally had to put my phone in another room to concentrate on what I was reading – including, ironically, Haidt’s book. Otherwise, I found myself returning to my customary middle-aged sites: realestate.com, YouTube and the Sydney Morning Herald. I can spend the last 15 minutes of my night scrolling through an Instagram feed so banal I can literally feel my IQ going down as I watch another dog on a skateboard. But at least I am an adult. My brain is not growing like crazy like a young person’s. I can scroll, just like I can do other addictive things I wouldn’t let a thirteen year old do such as drink alcohol or buy a lottery ticket.

Boys are also particularly susceptible to endless gaming that disconnects them from the real world. In moderation, with real friends online, I don’t think gaming is a bad thing, although it is not to my own taste. But playing deep into the night, or as a replacement for meeting in real life and enjoying the sun is a serious problem. Exposure to pornography and extreme viewpoints that feed a sense of grievance deserve articles all their own.

Haidt’s book The Anxious Generation includes an excellent analysis of this. Jonathan Hari’s Stolen Focus (2022) and Jean Twenge’s IGen (2017) also contain a mine of information.

In one sense we have heard all this before. Little I have written will come as a shock. What Haidt does show, however, is the disturbing evidence that these influences are literally rewiring the teenage brain. He calls it the ‘Great Rewiring’ of 2012-2017. We are dealing with something that has far more damaging effects than we even thought only six years ago when our Deputy Headmaster Andy Quinane and others at Newington restricted mobiles around the school (the school I was at – Oxley – did the same thing).

A phone can be useful. It can be a good way to find out information, tell you about the train, stay in touch with family and news, catch an Uber, pay bills or to work out where to meet. Hey, if you get lost in the jungle in the dead of night you can even use the flashlight.

But the anxiety creating, vapid and algorithmically pernicious effects of the social media apps on our children is a cause for real concern.

I will write again soon about things we can practically do about it.

Mr Michael Parker

Headmaster, Newington College

Image by Dave Cicirelli from https://www.anxiousgeneration.com/art#project