The War for Children’s Minds (and how we missed our stop)

Possibly the most influential single book I have read about education is The War for Children’s Minds by Stephen Law. Published in 2006 when the world was still coming to terms with the aftermath of 9/11, it contained urgent pleas for how to teach ideas, morals and ethics. Back in 2006 it really amplified and solidified for me the work I had been doing with ‘philosophy for children’ and critical thinking in the previous decade. Seventeen years later, I am delighted that Stephen Law is Newington’s Thinker in Residence for a week starting today. You might see me in the next week trying to get him to tell me about his new book, or have coffee with me at a café, or just sign my shirt.

Law is the Director of Philosophy at The Department of Continuing Education, University of Oxford and the author of a dozen books about popular Philosophy including The Philosophy Gym and The Philosophy Files. He is giving a talk about critical thinking at our Ethics Centre on Wednesday night (tickets available from Eventbrite), spending each day in various classes, presenting a Professional Development afternoon to our whole staff and presenting for a whole day on critical thinking to key staff members. The War for Children’s Minds was written before the advent of social media and could not take account of the coarsening of public discourse that stemmed from that. However, his approach is still very influential on our own development of our Critical Thinking quarters and our outlook in classes.

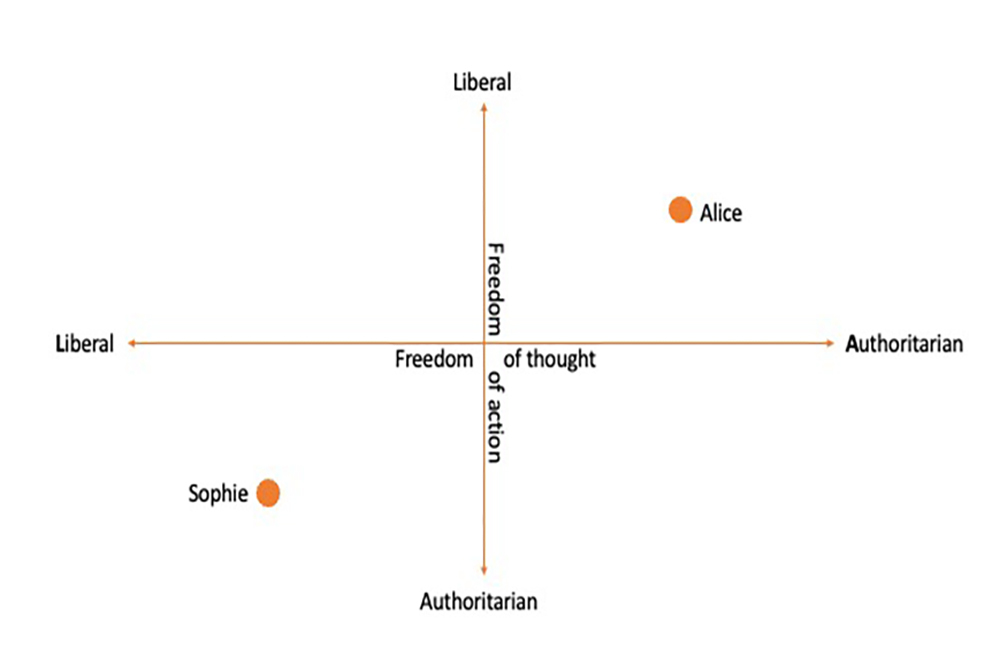

The War for Children’s Minds starts off with the war between authoritarian (think what I tell you to) and liberal (think for yourself) outlooks on raising children. He writes about how much freedom of thought a child should have, but then makes a big distinction between that and how much freedom of action a child should have. He ends up graphing it (p16) like this:

In his graph, Alice – top right – as a parent is very liberal (indeed permissive) with her actions, but authoritarian in her thoughts. Her son can get away with all sorts of bad, spoilt and generally horrid behaviour from day to day, but is howled down by his mother if he dares to question the family’s religious faith or political views. On the other hand, Sophie – bottom left – imposes quite an authoritarian set of rules on her son, expecting him to be on time for everything, have his room spotlessly cleaned and graciously serve canapes on a tray to visiting family friends. However, she also encourages her son to question the rules if he thinks them unfair and she commits to taking his views seriously. She is willing to listen and discuss, even if she doesn’t end up agreeing with him or changing the rules. She is liberal in thought and authoritarian in action.

Stephen Law thinks schools should operate like this too – encouraging freedom of thought and the ability to disagree in a structured way, but still expecting students to adhere to rules. I like to think that the way we handled haircuts at Newington last year was an example of this. The students voted for a SRC, the SRC made a carefully planned presentation to Pastoral Executive (that I was at) about how the haircuts rules should be relaxed, and we took their advice – despite some misgivings.

If students are going to think for themselves, they need tools to be able to do a decent job. There is better thinking and there is worse thinking. This is where our Critical Thinking Centre comes in. The Centre is at the beginning of teaching tools and strategies to our students that should last them a lifetime, so that they can responsibly think for themselves when they choose their degree, decide how to vote, make business decisions or simply decide what is right.

And this is where Stephen Law throws in the curve ball of moral relativism and tackles how to manage it. Moral relativism is not wanting to diminish anyone by calling their views into question, leading to a sort of ‘well I have my truth and you have your truth, and we can all get along happily’ approach. Law points out a variety of perverse documented results that come from this, including university students not wanting to condemn the Holocaust, apartheid or ethnic cleansing because ‘to pass judgement, they fear, is to be morally absolutists and having been taught that there are no absolutes, they now see any judgement as arbitrary, intolerant and authoritarian’ 1. I once taught a (very nice) class – not at this school – in which all but two students said that slavery could not be judged as bad because it was practised in Ancient Greece and we shouldn’t judge them.

Law then goes on to say that authoritarians trash liberals for being too morally relativistic, whilst moral relativists trash liberals for being too authoritarian. Classic liberal thinking gets slammed from both ends. Yet classic ‘liberal’ critical thinking is exactly where we should be.

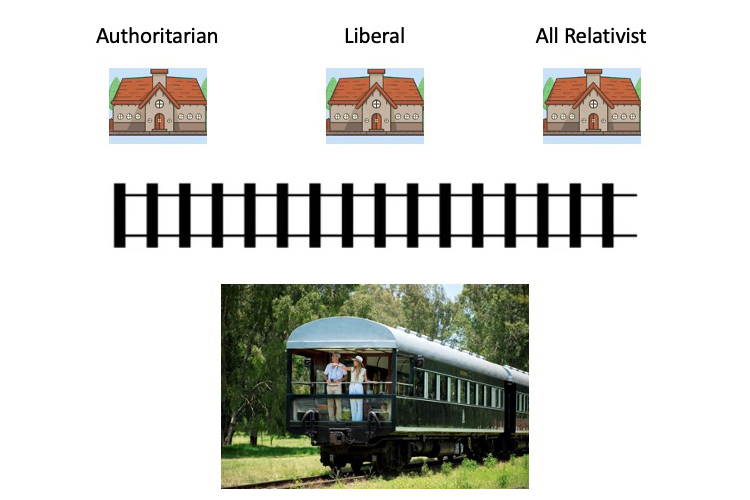

The way I see it is that if our ethical society is like a train journey then a lot of people missed their stop. Travelling out of Authoritarian land, some of us slept our way through Liberal Land and got out instead at Relativist Land.

Expanding on this point, as education became more enlightened, even in our own lifetimes, we moved from being told what to think to being told how to think. We travelled from the authoritarian station to the liberal one. The purpose of learning content was not just to parrot it off but to use it to form your own, well researched, well justified and well thought out personal views. This was hard work, but it would hold people in good stead for their lives. This was life in Liberal Land.

But for some of us, we didn’t want to get off at the liberal station, with all its freedom and responsibility mixed. Instead, we kept going to the easy, no-sweat, ‘you have your view, I have mine – or even better, I won’t have a view – and float along’ station. This is extreme moral relativism and allows the worst things to grow in its rampantly tolerant mix. Perhaps fascism, perhaps individual selfishness, perhaps torture, perhaps slavery. We missed our stop.

And so, to extend the metaphor to breaking point, some people (without realising it) stayed on the train as it turned around and went back to the authoritarian origin. I believe this is linked to the rise of social media and its pernicious effects on thoughtful public discourse. So now, in so many places, trying to problematise or question a point of view becomes a heresy and results in being vilified. Anyone can become an ideological fascist back at authoritarian station. It is slightly exciting and more than slightly scary to think about what the rise of generative AI is going to do and what train station it is going to favour.

In any case, the place that Stephen Law wants us to be, and the station that I want us to alight at, is the Liberal Station. A place where there is a diversity of well thought out views. A place where a gentle and sophisticated training of the head and the heart leads people to think carefully about morality, civics, religion, ethics and their own wellbeing. A place, dare I say it, that has our own Critical Thinking Quarters as its Station House and guiding light. I happen to think that a lot of schools are doing as good a job as possible at sustaining this for the next generation, and I like to think we are at the forefront of it.

It is terrific to have the author of The War for Children’s Minds as our Thinker in Residence at our Critical Thinking and Ethics Centre at Newington. Whether you see Stephen Wednesday night at the Ethics lecture, order one of his books or just hear from your child in the next few days, I hope this is just the start of your exposure to his outlook and approach.

By Mr Michael Parker

Headmaster