Curiosity

Dear Newington families,

It has been great to welcome your sons back to the campus. They always bring a freshness, an energy and interesting stories of the break (more Dubbo than Dubai this year, and quite a bit about the Netflix series they binged in isolation). Just about everyone seems rested and in good spirits.

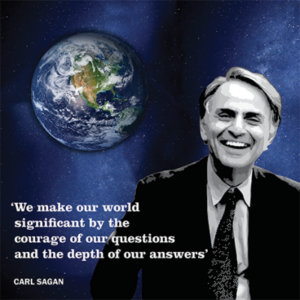

I spoke to senior school students today about the ‘Inspired Minds’ quality of curiosity and will be doing the same at the prep school campuses in the next week or two. I wanted to write something about it to you as well. We finished 2021 by announcing the opening of the Critical Thinking and Ethics Quarters and I referred quite a lot to the wonderful Carl Sagan quote ‘We make our world significant by the quality of our questions and the depths of our answers’.

We are now having a giant banner of it made for the Quarters. It looks like this image.

It’s doubling up as my desktop background to keep reminding me about what is important as we head into a new year.

Curiosity – asking good questions and being hungry for answers – is as important as rigour to be academically successful. This is easy to forget if you believe that doing well is only about working hard, chewing through the material and keeping your eye on the prize (which are all good things too). But curiosity is that spark that starts everything in the first place … and the bellows that keep a fire in the mind going. Curiosity makes things a passion not a chore, and an ends not just a means.

Studies back this up. Sophie Von Stumm, a lecturer in Psychology at Goldsmith University, led a review of research about what drove academic performance (1).She looked at 200 studies that took in 50,000 students. They worked out that curiosity was every bit as important as conscientiousness/rigour and ‘natural’ intelligence. Other meta-studies, including one at University College London, have found the same answer: curiosity is what Von Stumm calls the ‘third pillar’ of academic success.

Curiosity hasn’t always had a good rap. As explained by Ian Leslie in his excellent book Curiosity, it was revered in Ancient Greece as a form of happiness and play, but then squashed in medieval Europe (‘The Age of Danger’) to keep the masses poor, subjugated and ignorant. It sparked up again in the Renaissance and in the 18th century (‘The Age of Questions’) through the printed book, the newspaper and scientific societies. The bold questions people asked about the world led directly to the industrial, and eventually the technological, revolutions. Now we are in ‘The Age of Answers’, where technology and investigation has provided so much for us to explore and understand, and the capacity to both ask and find out.

Curiosity can be a question that already has a good answer, such as ‘how on earth do planes actually stay up?’ It can be a question that has no answer now, but may one day in the future, such as ‘how could we could stop a future coronavirus dead in its tracks?’ It could be a question that leads us to take action, or make a commitment: ‘why do so many people believe really crazy stuff?’ It might be a question that never will have an answer, but is brain-stretching to wonder about (‘would two plus two equal four if no-one in the world could count?’).

Nonetheless, we seem to have become less curious than a few hundred years ago. Ironically, technology may be at least partly to blame for this. As Ian Leslie recounts; ‘The discussion site Reddit recently posted the question; ‘If someone from the 1950s suddenly appeared, what would be the most difficult thing to explain to them about today?’. The most popular answer was ‘I possess a device in my pocket that is capable of accessing the entirety of information known to man. I use it to look at pictures of cats and get into arguments with strangers’.(2) More on that another time…

But for us, here, now at Newington, the fostering of curiosity is both powerful and vital. It is why I find so many classrooms exciting – because they are where these sparks of curiosity are going off and where these fires are being fanned. And wherever they are not, that is a real shame. The senior school staff spent some time last week getting professional development about critical thinking from the two Directors of the Critical Thinking and Ethics Quarters, Dr Jeremy Hall and Dr Britta Jensen. The junior school staff have been working on Philosophy lessons with Britta and will continue do so with our new recruit Kate Kennedy White, an expert in philosophy and children. Much of these sessions are about the quality of our questions. We have another whole day of professional development in this area in late March. We look forward to shining a light on where curiosity already inspired our lessons and working out where we can do more of it.

If curiosity is a third pillar of academic success, then we need to tend to it as much as hard work and rigour. Even if it wasn’t, then we would still want to fill the school with this trait for its own sake. Because curiosity is engaging, it is inspiring, and because it allows us to make our world significant indeed.

Kind regards

Michael Parker

Headmaster

(1) https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/1745691611421204

(2) Leslie, I. Curiosity, London, Quercus, 2014, p.129