AI and learning

During assembly last week I shared a video we produced to ‘announce’ the opening of our new AI gym with our Senior Prefect Jasper S.

The video showed how Jasper could make a full workout much easier by harnessing the power of AI, learning how to use prompts, and embracing the new technology to make his life easier. Indeed, it even gave him time to eat his lunch instead of doing some of the grunt work. If you are interested in the video, you can watch it here, and it only goes for two minutes.

Of course, the punchline is that while AI (in this case the two Deputy Senior Prefects) is making his life easier, he’s not doing the work.

The analogy between physical and mental work was obvious to the boys in front of me at that assembly. Although the brain is not actually a muscle, they share many of the same features. They need good food – either in the form of nutrition or content/ideas. Hard and varied work strengthens both our brains and muscles because they need to be stretched. Regular repeated practice is vital – we can’t just try a new exercise (or essay) once or twice and then think we have mastered it. Conversely, if we don’t stretch or workout our muscles and our brains, they either atrophy, or don’t develop properly in the first place.

Using AI to replace our work instead of assisting us, threatens the strength of our minds in the same way that the AI gym would threaten the strength of our bodies. Wrong use of AI is so, so, so alluring to young people (what would we have done as 14-year-olds if our homework could have been magically and undetectably done each night). But if AI is relied upon to do most of our children’s learning for them, it will eventually turn them as adults into not much more than cognitive human gloop.

Before I get too doom and gloom, a few caveats – AI is pretty extraordinary. It will become an intrinsic part of how we work, it will create enormous efficiencies, it is already saving lives, we need to learn how to use it, and it may just save our whole species (more on that in an article next week). But, right now, I am writing about the narrower issue of the process of teaching and developing the next generation of people in schools.

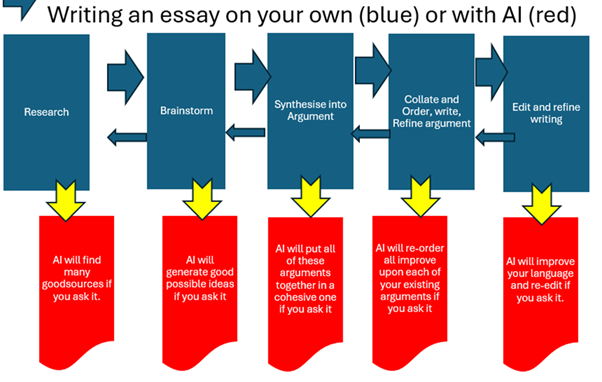

Let’s use the example of an essay on the causes of World War Two. History teachers don’t set essays on the causes of World War Two because they are lying awake at night wondering what the causes of World War Two are. The History teacher is setting the essay so that the kids can learn the process of researching, coming up with their own nuanced argument, drafting and editing. AI doesn’t just say ‘Let me write the whole thing for you’, it offers ‘help’ with each of those individual tasks, which sounds far more justifiable, indeed commendable.

I outlined it at assembly like this:

If AI assists someone by doing each of the red tasks, it will have, collectively, done the whole thing anyway. (Indeed many of us have already quickly normalised that it is reasonable for AI to ‘assist’, individually, with each of these tasks.) Repeat this AI generation for most essays, homework tasks, presentations etc, and the child will not have learnt how to do any of these things. This, in turn will lead to their intelligence becoming brittle, fragmented and not much use. This is, to say the least, a problem for education.

Indeed, in the writing of this letter to you, Microsoft copilot intruded and offered the following:

I can save you time and boost your creativity in several ways, including:

- Drafting text from your outline or idea [ie it will organise and write the letter for me – I just have to jot down a few random thoughts]

- Rewriting your text for alternative phrasing or to change the tone [ie it will edit and polish the letter for me– no need for me to go over it three times]

- Summarising or answering questions about content in the document [ie it will do the research for me, instead of me trying to synthesise the five books I have read on AI in the last two years, as well as many articles]

Each one sounds individually alluring, but if I had taken up all these offers, you would not be reading something I had actually written. Or indeed had anything much to do with at all.

It’s not just the learning of writing that is at risk here, it is the learning how to think. Thinking – the processes of analysing, synthesising, summarising, forming conclusions, using evidence, applying logic and a hundred other things – is done through hard, interesting and repeated work. We have a whole Critical Thinking quarters devoted to it. Indeed, these skills are going to be more essential and fundamental for our children in the future. We need to ensure that our students do this again and again during their school day, and when doing their homework too. The process of being creative also relies on more than many people being fed the same ideas or prompts by an algorithm.

There are exciting AI products that supplement and stretch learning – creating Socratic discussions, personalising each student’s learning and providing feedback. However, there are the more ubiquitous, and more relied upon large language models that, with a couple of prompts, will do the learning work for you. Our children’s thinking is not something to be wholly outsourced by stealth.

I will write twice more over the next week about why I think that the AI challenge is such a fundamental one for schools, as well as to outline more about Newington’s overall approach as we navigate AI.

I finished the assembly speech by saying ‘if you wouldn’t use the AI gym for your body, don’t rely on AI to do the work of your mind’. I hope that this article though gives you the impetus to start up a conversation with your sons and your daughters about what they get AI to do, what they do themselves, how AI might help and or hinder, and maybe even whether they would use an AI gym.