By Taj Gupta

From classroom to courtroom, office to online shopping, it’s hard to deny the growing prevalence of artificial intelligence in our everyday lives. Now, unlike ever before, we’re less prone to making independent decisions than we are to consulting ChatGPT about every minute dilemma. But how did this sudden societal shift come to be? Has free thinking already become a thing of the past? And if, or rather, when AI progresses, what risk does it pose for humankind? Given the recent release of the startlingly capable GPT-5, questions like these are crucial to consider, even if they can’t be answered by a single 10-word prompt.

First of all, we’ll have to look at what the AI of today really is. ChatGPT, and other chatbots like Claude, DeepSeek, Copilot and Grok, are all large language models, or LLMs. Without getting too technical, LLMs are able to generate text through a procedure known as ‘natural language processing’ (NLP). First, they are trained on a large corpus of training data, often petabytes in size. This data is initially unlabelled and unstructured as part of the ‘unsupervised’ learning stage. Here, the LLM begins to derive relationships between a range of semantics. Later comes the ‘self-supervised’ learning stage, where the model is assisted in labelling different concepts.

However, the most fascinating part of the process is arguably when ‘transformer architecture’ is implemented. Much like a human brain, the model undergoes ‘deep learning’, assigning a score, called a token, to different items in order to define connections. It is for this reason that many LLMs are called generative pre-trained transformers, or… GPTs.

Now, while it may seem as though these vast technological advancements appeared out of nothing, progress within the field of AI and thinking machines in general has been underway for many years. Early notions of the ‘artificial human’ can, in fact, be traced back to ancient myths and medieval legends. One such example is that of the Greek and Egyptian automata — all-knowing androids that were said to answer any question presented to them. Later came the concept of the ‘homunculus’, a miniature, alchemised human, first appearing in Faust: The Second Part of the Tragedy. Yet, with the emergence of computer science around the 1940s and 50s, AI became a matter of serious scientific research rather than one of mere speculation. Experimentation had shown that the human brain transmits electrical signals as part of a large neurological network. This understanding was crucial to the development of information theory, which posited that digital signals could form the basis of an electronic brain.

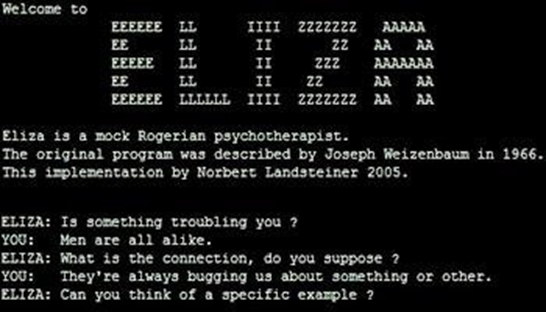

In 1966, such theories were actualised with the development of the first ever language model, named ‘Eliza’. Programmed by computer scientist Joseph Weizenbaum at MIT, Eliza possessed many of the key features of the language models we use today. Through primitive pattern matching, the chatbot was able to simulate conversations with users based on unique prompts. Importantly, Eliza was perhaps the first instance where a machine was able to attempt the Turing Test — the assessment of a computer’s ability to demonstrate intelligent, human-like behaviour. While such growth seemed promising, criticisms of the legitimacy and necessity of AI research led to a sharp decline in funding during the 1970s. This period is known as the AI winter.

Fortunately, with the 1980s came the introduction of ‘expert systems’ — AI applications that would mimic and respond to human experts in a given field. Because of these practical use cases, corporations poured millions of dollars into the AI industry, sparking a boom in research and innovation that continues to this day. Yet, the most significant breakthrough in arriving at modern-day LLMs came much later on. In 2017, Google released research on transformer architecture in a report titled Attention Is All You Need. From here, companies scrambled into action, fine-tuning code in an effort to be the first to publicly release a model. This, of course, all culminated in OpenAI’s groundbreaking launch of ChatGPT on 30 November 2022.

Naturally, this rapid progression within such a short amount of time begs the question: how far can this technology go? To answer that, it’s important to understand the difference between various forms of AI. Experts argue that even the most advanced LLMs of today still fit under the category of Artificial Narrow Intelligence (ANI). This is to say they are only capable of handling specific tasks, much like CAPTCHA systems and facial recognition software. For a model to be considered Artificial General Intelligence (AGI), it would need to perform virtually every cognitive task at the same level or better than the very brightest humans in a given field. With each new model, prospects of an AGI become nearer and nearer to reality. In fact, OpenAI’s CEO Sam Altman has heralded GPT-5 as the most significant development towards AGI yet.

However, there’s another clear distinction to make, and that’s between AGI and Artificial Superintelligence (ASI). Unlike an AGI, an ASI would be able to surpass human intelligence in every meaningful way. This is, thankfully, still hypothetical and has been the subject of science fiction for years. Yet that isn’t to say it would be impossible to construct an ASI in the far future. If this is the case, there are a number of potentially dangerous ramifications to consider, both social and ethical. For one, we are already witnessing threats to employment — many non-physical jobs, especially those that require automation, can be performed faster and more efficiently by AI agents. Interpreters, translators and accountants are professions that are perhaps at the greatest risk. With the advent of an ASI, these consequences would reach unprecedented levels.

If we are to consider a level of superintelligence, we must also assume a certain level of sentience. This is, undoubtedly, the most alarming aspect of an ASI. Originating in a 2010 web forum, Roko’s Basilisk is a philosophical thought experiment that explores these ideas. Imagine, some time in the future, there is an artificial superintelligence that has the ability to punish any person who knew of its potential existence but chose not to support its development. Under this logic, anyone — even the people of today — could be punished. This idea, while outlandish and likely inconsequential, can be somewhat unsettling.

Ultimately, as our world becomes more and more AI-centric, it is important to step back and challenge ourselves to think critically — to complete tasks without the help of ever-so-convenient LLMs. Equally, it is important to consider and appreciate that which makes us uniquely human — anger, empathy, compassion and the ability to make mistakes. However advanced AI becomes, we can at least seek solace in knowing these are qualities it will never be able to replicate.