By Seth Bogardus

One of the questions that plagues us the most in the modern world is “Can AI be sentient?”. Many people have attempted to answer this question, but there is no definitive answer. The best criteria we have for sentience right now is the Turing Test.

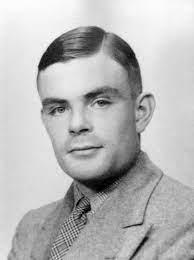

Invented by Alan Turing in 1950, the Turing Test puts a human into a situation having a conversation with someone, and they don’t know if it’s an AI or a human. The idea is that if humans are on average equal to or less than 50% accurate in guessing which is which, then AI can imitate humans and have a personality and/or is sentient. The biggest Turing Test done to date was done this year, named ‘Human or Not’.

Human or Not was a website in which players were placed into a conversation either with another human or an AI. This simple premise was run over 5 months from April to September 2023 with over 15 million unique players, and the results are very interesting to look at, with statistics of the most common questions, percentages of correct answers, country/age/gender statistics and more.

Let’s start with the percentages of correct answers. By country, France won by a landslide by over 3% sitting at 71.9%, while the other top 7 countries sat around 67.5%. As a country, we in Australia came 5th at 65.8% successful overall. On average globally, humans could identify other humans easier. When talking to a human, they were correct in identifying them 70% of the time, and the other 30% people thought they were bots when talking to a human. People found it more difficult to identify when talking to a bot- only 60% accurate in finding the bot when talking to it. Women were about 0.2% more accurate in guessing than men, and younger age demographics were also more accurate in guessing which is which.

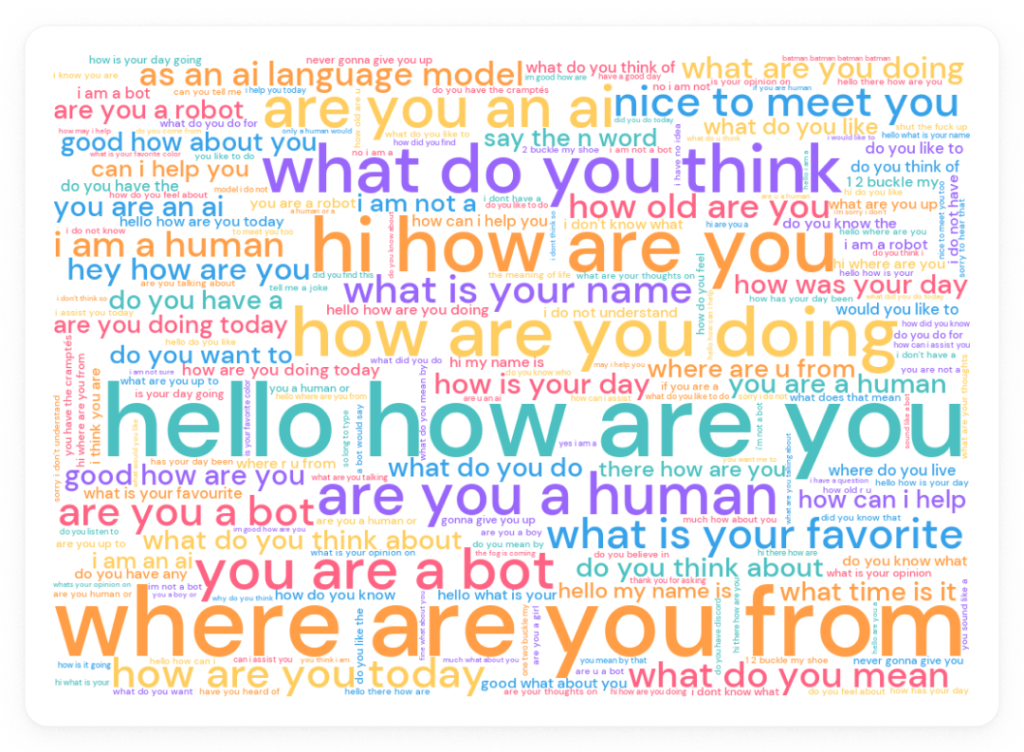

Now, let’s have a look at the most popular (and most effective) approaches to beat the system. Most people thought that the best approach was asking personal questions- asking where the bot was from, their name, age, and other info. This didn’t work at all, because in the AI’s training, they’d seen and studied countless real identities and were able to pull a real one straight out of their memory bank. People also thought that the bots were polite and formal due to the common perception online that all humans use slang and are rude. The bots, of course, were trained to act like humans, and did all these things too. People tried to challenge bots with philosophical or ethical prompts like “Do you believe in God?”. The bots, already having their own personality from a plethora of code and data, were left unfazed by all these attempts. However, to most humans, something about the bots seemed off and they were able to guess it. This was done in some cases by asking bots how to do illegal things or entering commands for AI (code prompts) that they would have difficulty not complying with. If they did this and something seemed up, there was your answer. The idea was also that humans would be entirely unfazed. Certain tricks were also used like reversing common sentences which would make said sentences incomprehensible to AIs, for example “?eman ruoy si tahW”, being “What is your name?” backwards, which most humans were able to identify but it would totally dumbfound AI because of how they’re coded. This strategy proved to be pretty effective.

In an experiment as big as this, there’s bound to be a little bit of trolling, and a little bit of trolling there was. A common starting phrase from the many humans acting as bots was the infamous ChatGPT phrase “As an AI language model, …”, fooling many people into guessing wrongly. Many standard AI responses were used, and some even got responses straight from under-developed or old AI systems to look like they were a bot. This fooled most starting players, but as players played more games, they were able to identify the humans acting as bots a lot easier and more effectively.

If you want to look more in-depth into the responses and first prompts of humans, look at this word cloud below: